Stomach issues/GERD/Ulcers/Reflux/Hiatal Hernia/STRESS !!!!

Proton-Pump Inhibitors May Boost Death Risk in Inpatients

IF YOU CHECK MY BLOGS AND ARTICLES I HAVE WARNED OF THIS YEARS AGO..THE OVER PRESCRIBED PPI’s AS WELL AS ACID BLOCKERS FOR GASTRIC ISSUES…THERE ARE SAFER , MUCH SAFER ALTERNATIVES

Proton-Pump Inhibitors May Boost Death Risk in Inpatients

Marcia Frellick

November 12, 2015

(other articles about PPI’s : Chronic Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors Increases Heart Risk

Continued PPI Use Boosts Risk of Repeat C. Difficile Infection

Proton Pump Inhibitors Do Not Ease Crying, Fussing in Infants and EXAMPLES OF PPI’S USED FOR GASTRIC PROBLEMS Clinically used proton pump inhibitors:

Omeprazole (OTC; brand names: Gasec, Losec, Prilosec, Zegerid, ocid, Lomac, Omepral, Zolppi, Omez, Omepep, UlcerGard, GastroGard, Altosec)

Lansoprazole (brand names: Prevacid, Zoton, Monolitum, Inhibitol, Levant, Lupizole)

Dexlansoprazole (brand name: Kapidex, Dexilant)

Esomeprazole (brand names: Nexium, Esotrex, esso)

Pantoprazole (brand names: Protonix, Somac, Forppi, Pantoloc, Pantozol, Pantomed, Zurcal, Zentro, Pan, Controloc, Tecta)

Rabeprazole (brand names: AcipHex, Pariet, Erraz, Zechin, Rabecid, Nzole-D, Rabeloc, Razo, Superia. Dorafem: combination with domperidone[citation needed]).

Ilaprazole (not FDA approved as of October 2013; brand names: Noltec, Yili’an, Ilapro, Lupilla, Adiza)

Proton-Pump Inhibitors May Boost Death Risk in Inpatients

Marcia Frellick

November 12, 2015

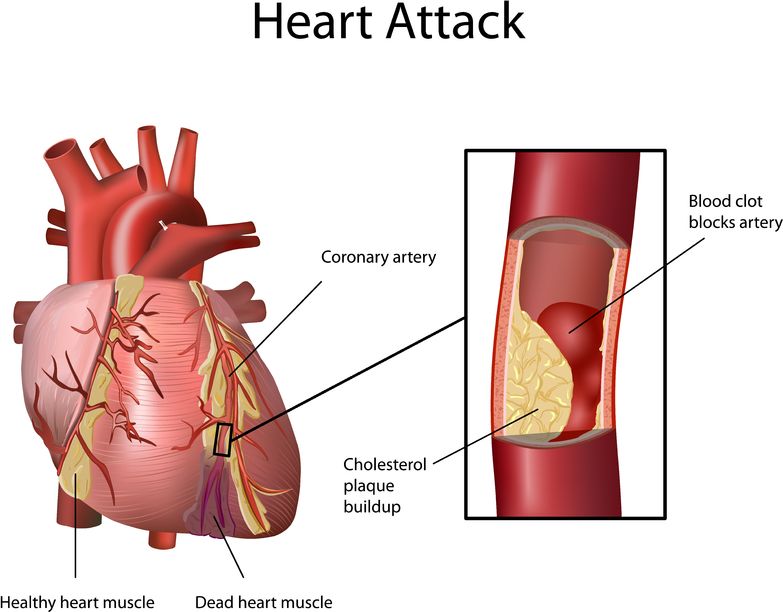

Proton-pump inhibitors are commonly used in hospitals to prevent gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, but may increase the risk of dying both for those who start use in the hospital and for those have used them before admission and continue use in the hospital, new data show.

Matt Pappas, MD, MPH, from the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Department of General Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, and colleagues say the increased risk for death comes because reducing acid in the stomach increases the risk for infections, especially pneumonia and Clostridium difficile (CDI), both of which pose a serious risk to hospitalized patients.

“Our new model allows us to compare that increased risk with the risk of upper GI bleeding. In general, it shows us that we’re exposing many inpatients to higher risk of death than they would otherwise have — and though it’s not a big effect, it is a consistent effect,” Dr Pappas said in a university news release. The authors published the results of their study online November 9 in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Given those findings, only those hospital patients at high risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) or mortality and at the very lowest risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and CDI should be considered for prophylactic PPI use against gastrointestinal bleeding, Dr Pappas said.

The researchers used a microsimulation model, using literature to determine risk estimates for UGIB, HAP, and CDI among inpatients, along with changes in risk with PPI use for each outcome.

New initiation of PPI led to an increase in hospital mortality in about 90% of simulated patients, the authors found. Continuing the drug on admission led to a net increase in hospital mortality in 79% of simulated patients who had been taking the drugs before admission. Results held with both one-way and multivariate sensitivity analyses. Net harm occurred in at least two thirds of patients in all scenarios.

“[I]n running our simulation, we thought we would find some populations such as those on steroids or other medications often prescribed together with PPIs, who would not experience the increased mortality risk,” Dr Pappas said in the news release. “But that turned out not to be the case.” Gastrointestinal bleeds are risky, but HAP and CDI are much more common, he added.

The authors say only two small controlled trials of prophylaxis exist in the inpatient population outside the intensive care unit. Therefore, evidence until this point has come largely from studies performed in intensive care units, where risk for UGIB is much higher because of the frequent presence of respiratory failure.

Limitations include that the study is based on modeling and relies on literature-derived estimates. In addition, distributions are fitted to published estimates and may not represent the patient population at any particular hospital.

Also, prospective risk assessments for UGIB, HAP, and CDI are limited, and although predictive models of UGIB have been retrospectively validated in multiple cohorts, they have not been prospectively validated.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

J Gen Intern Med. Published online November 9, 2015. Abstract